The 19th century French historian, Émile Chasles, in his book about Cervantes -- Michel de Cervantes, sa vie, son temps, son oeuvre politique et littéraire ("Miguel de Cervantes: His life, his time, his political and literary works") -- begins with an obligatory chapter or two about the great Spanish poet's youth and normally famous works (including the only one most people know now, Don Quixote). Then, starting with chapter three, he starts delving deep into Islam, for two whole chapters.

Chasles wonders if his readers, at that point, may ask why he is going off on this digression at such great length. He notes that actually, nobody seems to realize how central Islam was to the life of Cervantes:

"No one, to my knowledge at least, has recounted the struggle of Cervantes against Islamism."

(Note the term "Islamism". In the 19th century, this did not denote, as it does in our PC-MC-addled age, some fantasy construct unrelated to Islam; it was just another way of referring to the same thing.)

This lifelong struggle Cervantes had, Chasles goes on to say, is at best presented by writers and historians in disjointed fashion, as though a nuisance that intrudes on the narrative and must be dispensed with quickly to get back to the "true" Cervantes.

"Bizarre phenomenon! the greatest writer of Spain dedicated the better half of his life's work to express a certain truth... without pedantry, with an ardor sincerely naive in its conviction, with the vitality of impressions of an eyewitness: and this effort of this man of genius is ignored."

As for this primary perspective Cervantes attained about Islam, Chasles writes:

"The political evolution of Cervantes was not immediately formed; it grew through his decade of experience in battles [against Muslims], then of captivity (1570-1580), alongside Don Juan at Lepanto, at Navarin, at la Goulette, then amid the prisoners of Algiers..."

More generally, overarching this central framework of Islam in the life and work of Cervantes, Chasles remarks near the beginning of his book:

"His life was a shipwreck, and his works were so much flotsam."

This is the startling summation of his first five pages of description of how Cervantes in his later years, even though his Don Quixote was popular throughout Europe by that time, had fallen on hard times in a life of poverty and ignominy. He died, says Chasles, in 1616 without hardly anyone noting his passing, and during the entire 17th century, no one bothered to visit his grave, nor did anyone seem to care about his collected works or his biography -- well nigh even into Chasles's own century, the 19th. Though a few stabs had been taken toward a definitive biography by his time, he only cites one as approaching good scholarship in his estimation: that of the Spanish historian, Martín Fernández de Navarrete (also an officer of the Spanish Navy who, by the way, Wikipedia tells us, was involved in fighting Muslim pirates in the late 18th century), to whom he says he owes a debt of gratitude for helping pave the way with research on his subject.

About his own work on Cervantes, Chasles writes: "I would like to say a word about the method I follow in this work. It is simple. I have tried to clarify the life of Cervantes through his fiction, and to explain his fiction by means of the circumstances of his life."

To begin this task, says Chasles, "let us put Cervantes back into his age". What does he mean by this? The dates of the long publication of Don Quixote, 1605-1615 (it took him ten years to get parts one and two out, a year before he died) are deceiving, says Chasles. In fact, Cervantes was not really a man of the 17th century, but a man of the prior century, the 16th. Thus, Chasles finds significant such experiences as his travels in North Africa in the time when King Sebastian of Portugal was fighting against Muslims of Morocco; not to mention his noble military service against Muslims in various parts of the Mediterranean, including, as mentioned above, during one of the great battles of the West against Muslims -- the Battle of Lepanto (1571), under the command of Lopez de Figueroa and along with the great Don Juan:

"Brother-in-arms with such men, an eyewitness to their exploits, a humble participant in their illustrious battles, he was from the beginning a soldier who never dreamed at the end of his life he would write Don Quixote."

Concerning Don Juan and his brave exploits against the Mohammedan scourge, Chasles quotes Herrera's Ode:

"That God will no longer suffer that Zion, so loved by Him, live any longer in this Babylonian Captivity."

Que Dios no sufre ya en Babel cautiva

Que su Sion querida siempre viva.

† † † † †

Alas, I must abridge this essay here well before the massive treatment I envision that would do Chasles' study justice. Given the sheer quantity and complexity of material he set forth, with which I will have to grapple, I may have to publish small doses at a time, at long intervals. I've already waited quite a while just to post this one here. My previous essays on this:

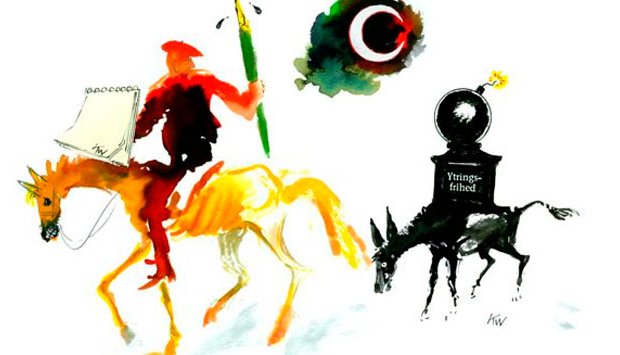

Tilting at windwills

2 comments:

I’m following along. Looking forward to the rest Hesp.

Thanks Fiqh. Part of my inhibition is that I have a tendency to think I have to polish everything in a framework. If I just post the relevant material without polish, it would still be useful, perhaps. We'll see...

Post a Comment